Ten years ago, The New York Times published the findings of Google’s Project Aristotle. If the study name doesn’t ring any bells, I bet you’ve heard of the term “psychological safety”. It was one of the 5 core ingredients of the secret sauce of Google’s high-performing teams, and a final nail in the coffin of the old school approach of valuing who is on the team over how the teams work. Since then, we have seen a true revolution in management theory, moving away from the industrial command-and-control to a more empathetic, human-centric approach.

Today, the landscape is shifting violently, once again. We are now managing humans, augmented by AI, integrating Gen Z workforce, and navigating the friction of the Return-To-Office mandates. In the quest for creating high-performance teams, the question of 2026 is no longer “does culture matter?”, it’s “how do we scale it?”

Nobody taught me how to be a good leader. Just like most, I used my intuition, mimicking or rejecting the leadership style I experienced myself. A decade later, I have come to my own framework that was forged in the fires of my own successes, and — most importantly — failures.

I’m not interested in sharing yet another theoretical framework. What I do want to do is open my vast library of resources I’ve been collecting over the years: specific instruments, meeting templates, team cadences, growth plans, and communication scripts. To do that, I need to paint the picture of where they came from and how to make the most of it.

I feel extremely lucky to live in this particular time in the history of organizational psychology and management theory evolution. It’s like timing a wave: catch it too early and you’re ahead of the break; too late and you’ve missed the momentum.

What I’ve designed is built on the shoulders of giants. Let’s take a quick stroll down the history lane, so you understand the context and the evolution of the logic behind it.

The history of management theory started with factories and the rise of the industrial workforce. Scientific Management (aka Taylorism) was the dominant operating system, where business was a machine and employees were cogs — a replaceable component valued for compliance. The underlying assumption was that people were inherently lazy, but could be motivated by carrots and punished with sticks.

As the economy shifted from industrial production to intellectual work, this binary model of reward and punishment was challenged by Self-Determination Theory (SDT), popularized by Daniel Pink in 2009, when he published Drive: The Surprising Truth About What Motivates Us. He argued that, once the baseline of fair compensation is met, there are three factors that will lead to deep professional engagement: Autonomy, Mastery, and Purpose.

It was a turning point that intuitively resonated with frustrated managers and disengaged employees; however, it lacked the rigorous, real-world data that could prove that this approach to team design is financially profitable and sustainable.

Project Aristotle, launched in 2012, provided exactly that. Using double-blind interviews of 200+ employees, they studied 180 teams (115 in engineering and 65 in sales) trying to answer a deceptively simple question: What makes a team effective at Google?. The initial results refuted the original hypothesis that it’s a mix of individual traits and skills that makes those teams effective. What they found was that who is on the team matters less than how the team members interact, structure their work, and view their contributions. They came out with their own framework of five key dynamics:

This study was truly revolutionary — it finally quantified the impact of “soft” skills that technical professionals often dismissed. It shifted our focus from hiring the smartest people to those who can build safe team environments.

The next logical step was operationalizing these findings. How exactly do you foster psychological safety? Enter the stage: Kim Scott’s Radical Candorand Amy Edmondson’s The Fearless Organization.

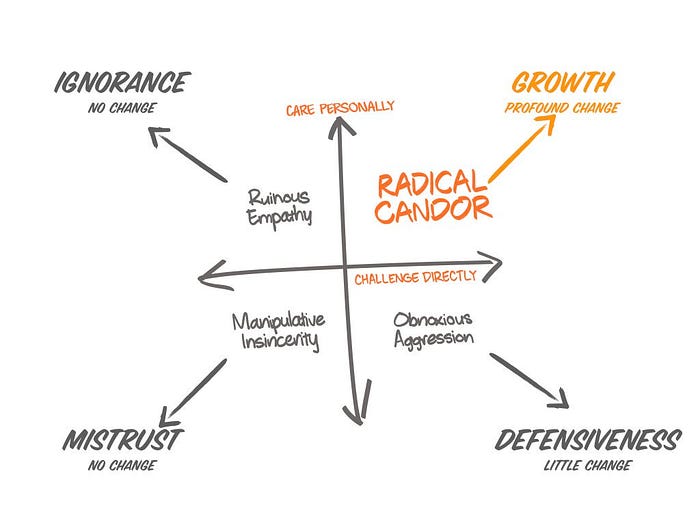

Kim Scott is a former Google and Apple executive, who published a tactical guide to building relationships. Her four-quadrant framework mapped management styles across a human dimension of Care Personally and performance dimension Challenge Directly, arguing that effective leaders should be in the High Care / High Challenge quadrant: feedback is given with a genuine intention of helping a person grow, so it’s specific, sincere, and kind, while not shying away from the truth. The nuance was in the implementation, where the “care” component was a critical prerequisite. Without it, a “brutally honest” feedback would be perceived as a threat and cannot be processed effectively.

Unlike Scott, Amy Edmondston (whos academic work underpinned Project Aristotle) focused on the organizational level. She published The Fearless Organization in 2018 and offered a key distinction: psychological safety does not mean comfort zone.

The Learning Zone (high psychological safety + high standards) is where you want your team to be. High standards drive high effort, and high safety allows for risk-taking. Probably the best example was Edmondson’s research in hospitals, where on unsafe teams, nurses and doctors hid errors to avoid punishment, leading to systemic risks. On safe teams, errors were reported immediately, treated as data, and used to improve the system. This “reporting culture” is the hallmark of the Fearless Organization and is essential for any industry where “workarounds” (fixing a problem without reporting it) can lead to disaster.

By 2020, a model for creating a high-performing team was formed: the ideal leader fosters psychological safety through radical candor, operating within an agile structure with a servant leadership style.

The COVID-19 pandemic put this framework to a rigorous stress test. Remote work made autonomy a logical necessity, trust became the primary currency of leadership, psychological safety became one of the core factors in employee retention.

This brings us to today.

The future of leadership is facing a few new challenges:

While we can philosophically debate all these factors, one thing remains clear: building and scaling high-performance teams is now a baseline expectation for any leadership role.

Psychologists Deci and Ryan gave us the original ARC (Autonomy, Relatedness, Competence). But in the context of 2026 leadership, we need an upgrade. My ARC 2.0 is built on a foundation of Structure & Clarity (a non-negotiable requirement, without which everything falls apart), supporting upgraded pillars: Authenticity, Refinement, Connection.

This is a box, within which you get to have freedom of co-creation, innovation, and creativity. Boundaries, norms, and principles should become axioms; the cornerstone of your home. As Project Aristotle identified, it’s the 3rd most important dynamic, yet often the most neglected. Without this foundation, psychological safety devolves into anxiety, and autonomy becomes confusion. This is the starting point for every leader:

In ARC 1.0, the “A” stood for Autonomy. In ARC 2.0, I argue that you cannot give autonomy until you have established Authenticity. Authenticity is the antidote to the corporate “professional” mask and the slow accumulation of burnout. We are astonishingly good at identifying inauthenticity at a subconscious level; and when we do, it erodes our trust. So to build psychological safety and trust, you need to be authentic.

In ARC 1.0, “Competence” was a static state. In ARC 2.0, we adopt Refinement — a dynamic process of continuous improvement. It draws on the Japanese concept of Kaizen — small incremental improvements compounding into marginal gains — and the assumption that employees intrinsically want to become better at their craft.

In ARC 1.0, “Relatedness” was a psychological need. In ARC 2.0, Connectionis a strategic lever to ensure retention and engagement. One of our core needs is a sense of belonging that gets amplified in the era of remote and hybrid teams.

These pillars and their components intertwine and support each other. For example, peer connection strengthens dependability; vulnerability makes feedback loop effective, which, in turn, accelerates mastery of craft.

We are entering a new era of radical efficiency. With it, comes an end to the notion that “soft” skills are optional. Leadership is not a soft skill; it’s a technical discipline and the essential infrastructure to creating and scaling high-performance teams. It’s time we treated it as such.

Now that the theoretical ground is out of the way, I can share the “how”. In the coming weeks, I’ll be releasing my toolkit. It’s functional, modular, and designed for immediate deployment. I’m sharing it to establish a new standard and help leaders — like you — be more efficient.

I am also looking for critical feedback loops. Don’t just tell me you like it; tell me where the logic fails under pressure and where it drives measurable results.